Protected bike lanes have been proven again and again as the best approach for making streets safe and comfortable for biking. People of all ages and abilities get excited about biking when they are physically protected from car traffic.

This protected biking environment dramatically increases safety and comfort for people on two wheels while having limited negative impact on car and truck traffic.

The key ingredient for a good protected bike lane (PBL) is a street with space that can be dedicated to bikes. While not all streets will work, there are more than enough streets in Chicago for a robust network of PBLs.

In some cases adding a PBL requires re-allocating street space from cars, such as converting parking or travel lanes. This can be difficult without strong community and government leadership.

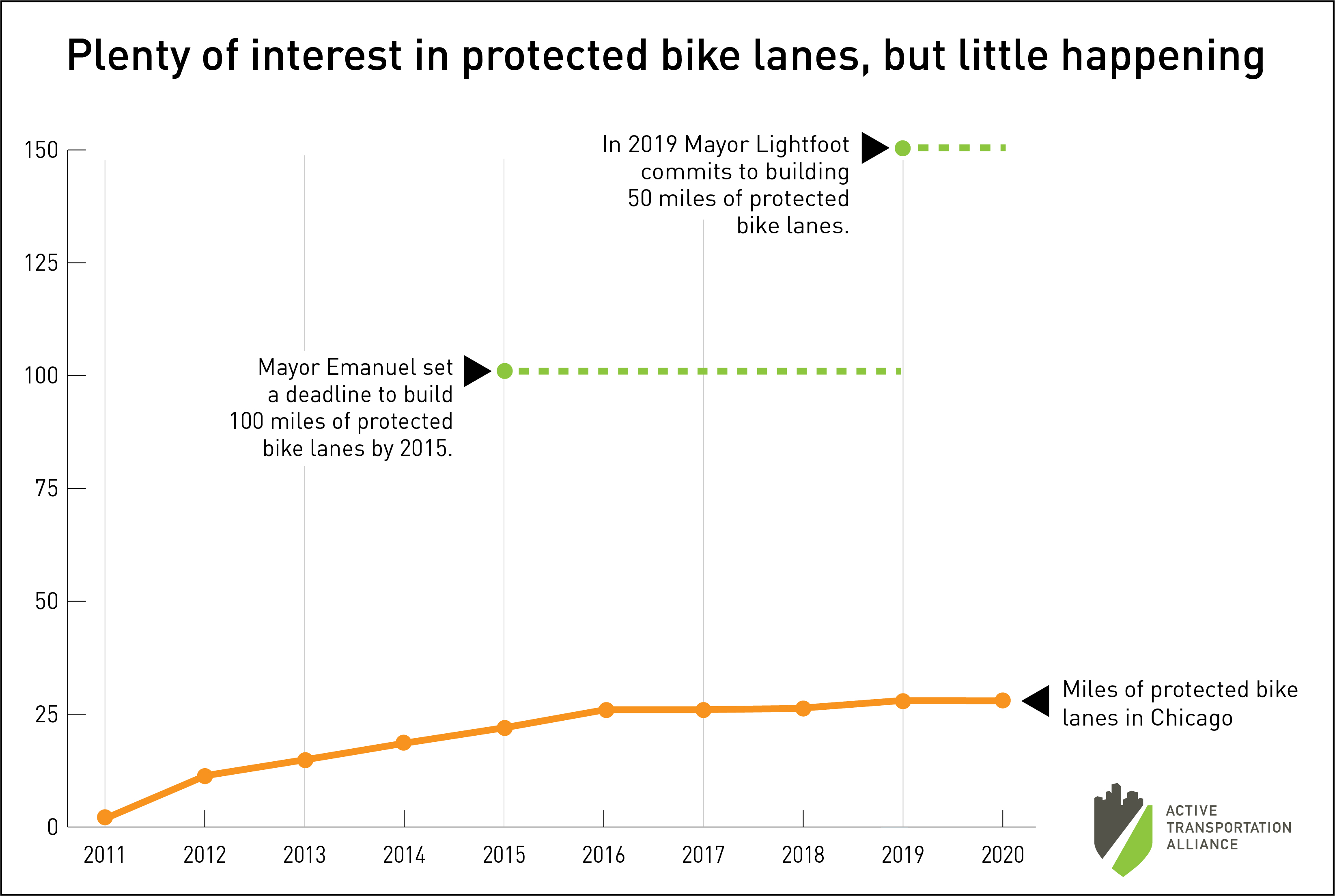

Fortunately, more of our elected officials have come to appreciate the many benefits of PBLs. A growing coalition of Chicago City Council members are actively calling for more bike infrastructure in their wards. And the Lightfoot and Emanuel administrations both committed to adding more than 100 miles of low-stress bikeways over their four-year terms.

Yet, PBLs remain scarce and so many streets remain uncomfortable for biking.

And the meager number of Chicago streets with PBLs is not the only problem. Existing bike infrastructure isn’t equitably distributed.

Black and Brown communities on the South and West Sides have fewer miles of PBLs despite destinations being further apart and traffic crashes disproportionately happening in these areas.

So when we talk about new PBLs, we must distribute those PBLs equitably.

So why are we settling for painted bike lanes when we know physically protected lanes deliver major safety benefits and will get more people riding? Why all this apparent interest, but so little happening?

We’ve outlined four of the biggest barriers to building a network of safe and comfortable bikeways on Chicago streets and suggest ways to address the barriers.

![]()

PROBLEM: Lack of dedicated capital funding

The Chicago Department of Transportation adopted a strong Complete Streets policy, bike plan (that was scheduled be complete by 2020), and Vision Zero Action Plan to eliminate traffic fatalities and serious injuries by 2026. While each of these plans and policies represent an important step, they’ve floundered because no dedicated funding exists for implementation.

In order to build the high-quality infrastructure necessary to reduce crashes and save lives, we need a consistent, reliable source of local funds. While the cost of building PBLs is a drop in the bucket compared to building roads, PBLs do require more resources than standard lower-quality bike lanes because more outreach, engineering, and materials are required.

Currently, city officials rely on limited, local discretionary funds and inconsistent, highly competitive state and federal funds to fund PBLs. While all Chicago aldermen have $1.32 million in “menu money” to spend on infrastructure projects in their ward — including new bike lanes — other spending priorities often win out.

As a result, very little ward-based menu money gets spent on bikeways improvements citywide. When bike improvements are funded, they’re often lower quality painted lanes that are relatively cheap and easy to plan.

Overall, menu money is wholly insufficient to meet the need and demand for PBLs. Similarly, relying on competitive federal and state grant programs to fund the network leads to an uncertain, patchwork approach that is wholly contingent on grant application success. These programs also require a signficant local contribution, so any dedicated funding in Chicago could be leveraged for additional federal and state dollars.

SOLUTION: Create a $20 million Chicago Safe Streets Fund that is dedicated annually to new walking and biking infrastructure, with priority given to high-crash corridors on the South and West Sides.

PROBLEM: Staffing shortage at the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT)

Planning high-quality bike facilities requires design and engineering resources that are often in short supply at CDOT. Adding a painted bike lane to a street resurfacing project that’s already in the works is an easier technical task than to initiate a new project to build a PBL.

The department currently has one full-time city planner dedicated to advancing Vision Zero infrastructure projects and the city’s bike and pedestrian program. Additional work is assigned to consultants through contracts that come and go and don’t provide the stability that’s necessary for long-term planning.

These staffing levels pale in comparison to peer cities that have well-staffed departments of planners and engineers dedicated to advancing safe streets work. If building safer streets and more protected bike lanes are city priorities, as elected officials say they are, Chicago needs to hire the staff to do the work.

SOLUTION: Fund several new full-time positions at CDOT, including more bike, pedestrian, and public transit planners and at least two new traffic engineers.

PROBLEM: Lack of cooperation from Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT) on state roadways

A recent report from the Safe Routes Partnership shows how dramatically Illinois has fallen behind other states in creating strong policies that improve conditions for walking and biking. This is demonstrated in the state’s Complete Streets law, which lacks teeth and allows IDOT to use poorly defined “exceptions” to get around the requirements. The 2007 law has never been evaluated or reviewed to determine whether it’s leading to more infrastructure that creates safer streets being built, including PBLs.

In 2019, after much lobbying, IDOT’s design manual finally added PBLs as a recommended type of bikeway, though the department still rarely approves adding PBLs to state roads. In Chicago, many of the major streets that connect to popular destinations are state controlled. This results in many crosstown bike routes in the Streets for Cycling Plan essentially being off the table.

It also leaves largely untouched several of the city’s most dangerous streets, most of which are in Black and Brown communities on the South and West Sides. State-controlled streets routinely top the list for having the most crashes and serious injuries for all transportation modes.

SOLUTION: Pass legislation to strengthen the state’s Complete Streets law and elect more walking and biking champions to the state legislature to advance IDOT reform.

PROBLEM: Community and political opposition

There’s a perception among many advocates that community opposition is the main reason more bike lanes don’t get built. The reality is that structural barriers prevent most projects from ever getting to the final approval stage. When they do get to the approval stage, they’re often well received by community leaders and championed by local elected officials.

Still, opposition from residents and businesses can derail PBL projects. Concerns about lost or re-located parking and perceived traffic delays from converting travel lanes can drown out the safety and comfort benefits, even when these concerns are addressed in the project design. The city’s outreach resources are limited so the people and organizations with the time and energy to speak out on their own are heard the most under the current process. Meanwhile, the voices of people living in high-need Black and Brown communities on the South and West Sides are often overlooked.

Strong community-centered planning is critical to designing and building effective projects, especially when bike lanes are viewed as signs of gentrification in disinvested neighborhoods. But often CDOT and aldermanic outreach processes aren’t comprehensive and inclusive enough to generate useful community dialogue.

SOLUTIONS:

-

Strengthen CDOT community outreach processes through the lens of a comprehensive plan focused on racial equity. Require project managers to use a department-wide outreach process that is focused on racial equity.

-

Leverage existing community infrastructure like special service areas, neighborhood groups that serve as delegate agencies for the city, and park advisory councils.

-

Conduct Racial Equity Impact Assessments for major capital projects, like road reconstructions.

![]()

HOW YOU CAN HELP

- Take action now to support funding more protected bike lanes in Chicago’s 2021 budget.

- Share your thoughts and ideas about protected bike lanes challenges and possible solutions.

- Sign up as an Active Trans Ambassador to learn how to help lead the fight in your community.

- You can also join as an Active Trans member or sign up to receive updates and alerts about this issue.