It was a great loss to the world of sustainable transportation when John LaPlante died in March of COVID-19.

As someone who worked with John over a number of years, I wanted to provide a more detailed account of his impact locally and nationally.

You might not realize it, but you’ve likely benefited from John’s efforts to improve street design and safety for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users. And the effects of his work can be felt not just in Chicago.

After earning transportation engineering degrees from IIT and Northwestern, John started out as a summer intern in the Chicago Department of Public Works Bureau of Street Traffic in the early 1960s.

He was a multimodal planner before it was cool, starting with his advocacy for on-street bike facilities in the early 1970s. A total of 50 new miles of on-street bikeways was designated in 1972, including 35 miles of pilot on-street routes in two communities with the highest number of adult riders — Lincoln Park/Near North and Hyde Park, and two experimental exclusive bike lanes to serve downtown bicycle commuters.

In addition, the city worked to provide bike parking at five downtown parking structures, hosted events like the Raleigh Boul-Mich Bike Rally, a 50-mile bike race on downtown streets, and sponsored the Central Chicago Bike Trail, a six-mile, one way route winding through downtown and Near North on Sundays during August and September that was used by 350-600 bicyclists a day, including many families.

By the end of the 1970s, the city’s bikeway system had grown to 90 miles of on-street bike routes and off-street bike paths for both recreation and commuting. This strong interest in cycling in the 1970s, which John was in a position to address as Chief City Traffic Engineer, was driven by the energy crisis, high gas prices, and an increasing federal concern about air quality.

It laid the groundwork for the later blossoming of bicycling in Chicago in the 1990s, when the Mayor’s Bicycle Advisory Council was established and the Bike 2000 Plan, with the goal of making Chicago bicycle-friendly, was adopted.

John’s openness to new ideas and approaches and his interest in transit operations and the pedestrian experience came together in projects that pushed the envelope, sometimes successfully and other times as “learning experiences.”

These included contraflow bus lanes on Washington, Madison, Adams, and Jackson, which worked well for bus operations but were eventually replaced with concurrent bus lanes due to pedestrian safety concerns.

Another of these projects was the State Street transit mall, which started as a study that John played a key role in. While the transit mall was eventually replaced, features like wider sidewalks and Red Line entrance canopies and escalators still serve the public.

Another of these projects was the State Street transit mall, which started as a study that John played a key role in. While the transit mall was eventually replaced, features like wider sidewalks and Red Line entrance canopies and escalators still serve the public.

John had one of his greatest successes with another “mall” — the 1978 Lincoln Square “mall,” which rerouted Lincoln Avenue traffic to Western Avenue near Lawrence to create a pedestrian haven that became very popular, attracting unique businesses and crowds of people.

We now think of Lincoln Square as a great example of placemaking, but it was very controversial at the time. John developed the plan, performed all of the technical studies that showed the idea would work, and coordinated with businesses, the alderman, and other city agencies. Even today, CDOT is studying many other 5- and 6-leg intersections that would benefit from such redesign.

Beyond Chicago, John had a national impact on street design through his three decades on the AASHTO (American Assn. of State Highway and Transportation Officials) Green Book Committee and the Federal Highway Administration’s National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices.

The Green Book is “the bible” of street design. It started out as a guide for the design of rural highways, but later editions added guidance for urban streets. Unfortunately, even urban standards still reflect a bias towards drivers, versus the multimodal uses actually found on urban streets, where pedestrian and bicycle safety should trump traffic efficiency.

In his thoughtful, calm way, John fought against this bias throughout his decades of involvement on the national committees: he headed bicycle and pedestrian technical committees, helped develop the first AASHTO bicycle design guide, and served as principal author of the first pedestrian guide, and ensured that key recommendations of the guides were incorporated in the Green Book.

The results were real safety improvements for all street users. Key changes John advanced include:

- For traffic signal timing, reducing the assumed walking speed for people crossing a street from 4’ per second to 3.5’. Up to half of people starting to cross when the flashing “do not walk” phase began would still be in the street when conflicting traffic proceeded under the old standard. John showed that this standard was based on the average walking speed and did not take into account the slower walking speeds of the most vulnerable, including older people and people with disabilities.

- The requirement for countdown timers at all new pedestrian signals (and upgrade to countdown timers when signals are modernized). Fifty percent of Americans never understood the meaning of the flashing don’t walk, whereas the countdown timer is intuitively understood by people walking and driving, resulting in a 25 percent reduction in all crashes at corners where countdowns are installed.

Other changes he championed still have not been embraced by all in the field:

- Acceptance of the Green Book guidance that for urban streets, lane widths of 10, 11, and 12 feet are allowed (based on findings that these lane widths have no significant crash difference). Narrower lanes make it easier to retrofit city and suburban streets to complete streets, suitable for all users.

- Shifting the travel speed streets are designed for, from the current 85th percentile speed, the speed 85 percent of motorists feel most comfortable driving, to a target speed that takes into account the comfort and safety of pedestrians and bicyclists.

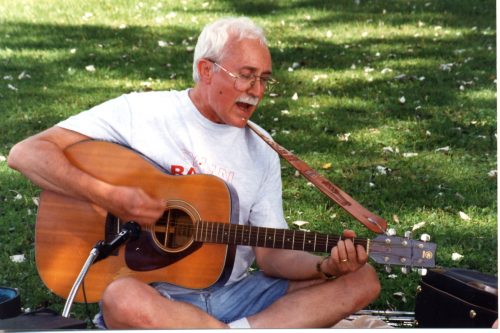

John played a key role in advancing complete streets locally and nationally, but he was not “all work and no play.” His colleague and friend Tom Kaeser summed it up: “John was a great friend as well as a great boss, fun to have a beer with, fellow softball player, a guitarist and singer at numerous professional functions. Needless to say, we’ll really miss him.”

This is a guest post authored by Luann Hamilton, who retired last year after working for 34 years in the Chicago Department of Transportation. She now serves on the board of directors of the Active Transportation Alliance. While writing this, she received input from John LaPlante’s longtime CDOT colleagues and friends Tom Kaeser and Chester Kropidlowski.

The LaPlante family is encouraging those who wish to make a charitable contribution in John’s memory to donate to Active Trans. Active Trans extends condolences to John’s family and is grateful for their support.

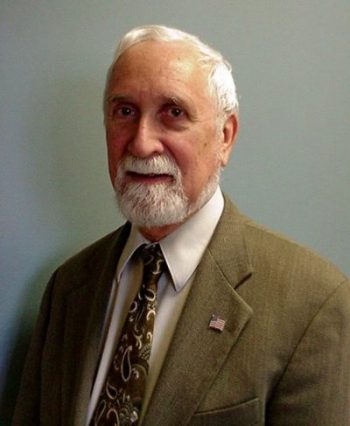

Top photo is John LaPlante; middle photo from a 1996 Chicagoland Bicycle Federation holiday party, from left, CBF President Greg Dreyer, Suzan Pinsof, and LaPlante; bottom photo shows LaPlante playing guitar. In 2008, CBF changed its name to the Active Transportation Alliance. Photos courtesy of Randy Neufeld and Chester Kropidlowski.